IAN SCLANDERS AUGUST 15 1952 MACLEAN’S MAGAZINE

ST. ANDREWS, N.B., has only fourteen hundred year-round residents. But its liquor store is reputed to sell more imported champagne than any other liquor store east of Montreal, and it has a grocer who stocks caviar and pâté de foie gras, a druggist who sells perfume at seventy five dollars an ounce, and two china dealers who offer dinner sets priced as high as two thousand dollars. The reason is that St. Andrews is the most fashionable resort on Canada’s Atlantic coast.

In this unusual little town, on a peninsula that juts into blue Passamaquoddy Bay, one of the major industries is barbering the tall cedar hedges which surround the estates of the rich with evergreen elegance. There are miles and miles of these hedges. They block the view at every tum, so when E. P. Taylor, the financier, was selecting a piece of property for a seaside retreat he studied the landscape from an airplane. As he circled over St. Andrews, on a sunny morning, typical “summer folks” were doing typical things.

Rt. Hon. C. D. Howe, in grey flannels and white shirt, was out on his broad lawn directing a team of gardeners. Senator Cairine Wilson, in a mud streaked cotton dress, was pruning rose bushes. At the Old Timers’ Club, H. D. Burns, chairman of the board of the Bank of Nova Scotia, and Lieutenant-Governor D. L. MacLaren of New Brunswick were playing a spirited game of cribbage.

Miss Olive Hosmer, whose father, the late Charles R. Hosmer, amassed one of this country’s fat fortunes, was out driving in her elderly Rolls Royce. Mrs. R. E. D. Redmond, a daughter of the late Lord Shaughnessy of the CPR, and Lady Davis, widow of Sir Mortimer Davis, were watching the bathers at the beach.

Noah Timmins, the mining magnate, and Sir James Dunn, the peppery old baronet who controls Algoma Steel and Canada Steamship Lines, were striding through elm-shaded lanes, while G. Blair Gordon (Dominion Textile) and Dr. Gavin Miller, noted Montreal surgeon, were shooting a round of golf. Howard W. Pillow (British American Banknote) and Harry W. Thorp (Murphy Paint) were swapping yams in the back room of Bobby Cockburn’s corner drugstore.

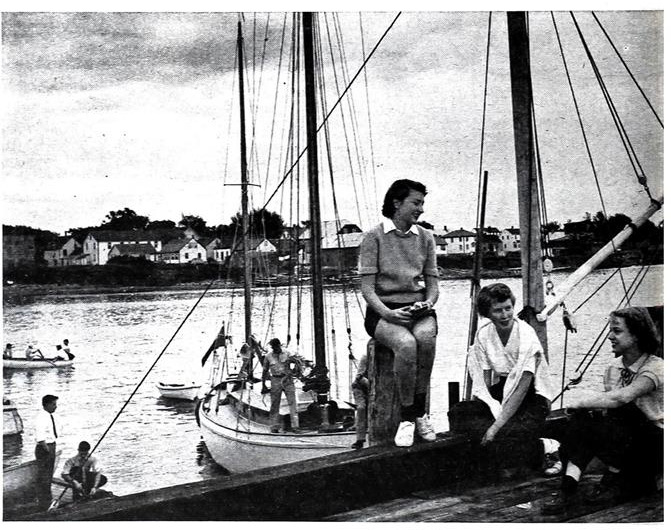

Scores of other upper-rung socialites were distorting themselves at St. Andrews. For St. Andrews, in the summer, is crowded with the kind of people who dress for dinner and describe their mansions as cottages. Year after year they turn up with their butlers, cooks, chauffeurs, limousines, rakish sport cars and yachts. They golf, swim, fish, sail and garden, and go to parties.

A musketball discarded by Champlain clinched Canada’s claim to St. Andrews. Since then this New Brunswick haven has lured a Bonaparte, two Fathers of Confederation, a parcel of peers and more millionaires per mile than any town in the land

There are parties morning, afternoon and evening, but these are polite and decorous, for most members of the St. Andrews set have reached or passed middle age and were either born with money or have had money long enough to avoid nouveau riche high jinks. They don’t swill champagne. They sip it. Nobody at St. Andrews has ever plunged fully clad into a swimming pool in a gay mad moment, and there hasn’t been a first-rate scandal since a prominent matron, out joy riding with a waiter, was killed in an accident. That was years ago.

Some vacationists find the place dull. A disappointed New Yorker complained to a desk clerk at the Algonquin—the posh but sedate CPR inn —that St. Andrews is “too damned refined.” But the majority of the summer folks prefer it like that. They frown on tourist traps that might draw a noisy element. When a dude ranch was opened by a promoter from Montreal—with beauteous Broadway cowgirls, Hollywood-style cowboys, and c floor show—they cold-shouldered it out of business in one season.

They’re so fond of St. Andrews, just the way it is, that they’re trying to keep it as changeless as possible in a changing world, a haven with the gracious manners and standards of yesteryear. They carefully preserve its scenery and traditions, shun modern architecture and fill their big houses with antiques.

In deference to their wishes the Algonquin, the pivot around which the social life revolves, hasn’t revised its menus noticeably for half a century. It still serves the elaborate kind of meals that have to be digested in an atmosphere of leisure. This hotel, which has two hundred and thirty rooms and two golf courses, didn’t discard the last of its Victorian brass bedsteads until 1951 because veteran guests had grown attached to them.

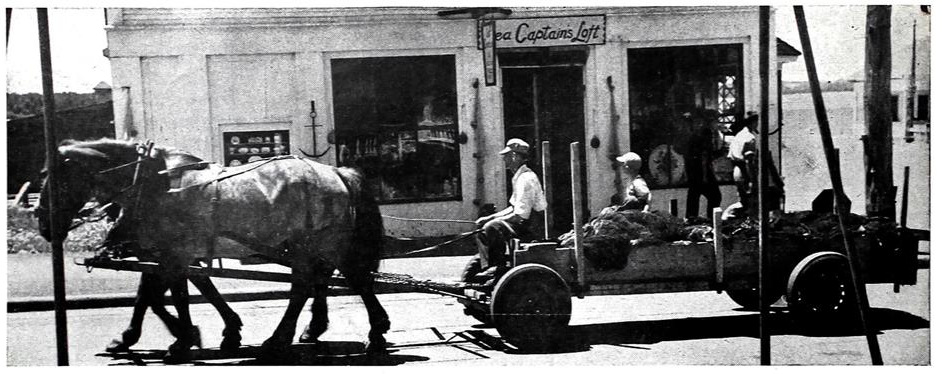

Under the New Brunswick Liquor Control Act, no drinks—not even beer—may be served in public places. Bars, cocktail lounges and beer parlors are illegal. The stately Algonquin has ignored this law and provincial authorities have ignored the Algonquin’s well-stocked mahogany bar—an old fashioned affair with a trapdoor leading to a wine cellar. There’s a rumor, which can’t be confirmed, that the Algonquin management told the N.B. Liquor Control Board once that if the hotel wasn’t allowed to serve drinks it would be closed down, with a loss to New Brunswick of a large and profitable slice of tourist business. Since then, according to the story, the Liquor Control Board has made no complaints. St. Andrews’ second hotel, the Commodore, decided that if the Algonquin could operate a bar the Commodore should be able to do the same thing. This worked for a while but, last year, the Commodore’s proprietor was arrested and fined five hundred dollars for being responsible for the illegal sale of liquor on premises. Residents of St. Andrews have an idea that the Commodore’s bar would have fared better had it been operated on the same lines as the Algonquin’s bar, which is so inconspicuous and quiet that you could hang around the hotel for a week with out knowing it was there. (Open to guests only. the bar is located below the lobby and reached by a stairway on the left-hand side of the lobby. Both the stairway and an outside entrance to the bar have no signs indicating where they lead.) St. Andrews, with its tide fiats, wooden jetties, sardine boats, lobster traps, golden sand, red cliffs and green slopes, casts a spell over many people. Field Marshal Lord Alexander, when he was governor-general, liked it so much that he stretched a scheduled stay of a fortnight into a month. David Walker, Scottish soldier and author, had a holiday at St. Andrews when he was in Canada before World War II as an side to Governor-General Lord Tweedsmuir. Captured at Dunkirk, he dreamed of St. Andrews when he was in a German prison camp and bought a house there when he was freed. His last two novels, Geordie, and The Pillar, were written at St. Andrews. The Rev. Henry Phipps Ross, a United States clergyman with inherited wealth, and Mrs. Ross, were so in love with St. Andrews that they insisted on being buried there. They left three hundred thousand dollars for the establishment of a library and museum at St. Andrews and a like amount for the district hospital. The Waycott trust, which maintains a public-health nurse, and the Harring. ton trust, which pays for Christmas parcels for the poor, were also set up by bequests from summer folks. Even crusty tycoons regard the town with misty-eyed sentiment. Men like Sir James Dunn provided the funds with which the Old Timers’ Club was built at the head of the public wharf. They wanted aged natives to have a cozy spot to meet and talk and play cards. Now they’ve formed a habit of dropping in themselves to enjoy the companionship of retired mariners and shermen, with whom they are on first name terms. The summer folks have i genuine affection for the natives and often show it with surprising gestures. When John Cadman Norris, St. Andrews’ only Negro, was old and infirm an anonymous Montreal industrialist worried about the fact that “Cady’s” home lacked indoor plumbing. He hired a contractor to add an up-to-date bath room to the bungalow. Cady. drove a team of truck horses on weekdays and pumped the organ in the Anglican church on Sundays. When he died in August 1948 the flags on the Algonquin and on the fancy estates were flown at half mast and the Hon. Marguerite Shaughnessy wrote a touching tribute which was published in the St. Croix Courier, the district weekly newspaper. A dozen millionaires were among those at the funeral. So strong is the charm of St. Andrews that a lot of summer folks put roots down there and think of it as their adopted home town rather than as a resort. Some of them, like Mrs. Redmond, Miss Shaughnessy, Sir .James and Lady Dunn, and David Walker now remain there all year. They take as much delight as the’ natives in the local legends and in the colorful characters of the past characters like Dr. John Calef, Robert Pagan, La Coote. the Rev. Samuel Andrews and Christopher Scott. Calef and Pagan. like the other founders of St. Andrews. were United Empire Loyalists. Exiled from the U. S. after the American Revolution they settled at Penobscot, expecting that Penobscot would remain under the British flag. When Penobscot turned out to be Maine they sawed their houses into sections, moved them to St. Andrews by schooner, and nailed them together again. The year was 1783. Calef, a medical pioneer, inoculated five hundred of his fellow citizens against smallpox soon afterward, and was pleased that only three of them died. St. Andrews was just getting on its feet when Maine raised an outcry about the boundary line. The Treaty of Paris stipulated that the border at this point should be the river where Champlain wintered on an island in 1604. It was generally supposed that this river had been the St. Croix, but Maine con tended that it was actually the Magaguadavic, thirty miles to the east. This would have placed St. Andrews within the U. S. Rut La Coote, a renegade French nobleman who had married an Indian, knew that Champlain had been on Dochets Island, in the St. Croix. He led Robert Pagan-a member of the New Brunswick .Assembly there and the two of them dug up a musket-ball, a metal spoon and a clay pitcher left by Champlain. This evidence kept St. Andrews in Canada.

Samuel Andrews, an Anglican clergyman who had been persecuted in New England as a Tory, stole the royal coat of arms of Wallingford, Conn., because he didn’t want it in the hands of rebels. He had it with him when he arrived at St. Andrews in 1786 and it hangs there today, in All Saints’ Church. Andrews lived on an island which has ever since been called Minister’s Island, and which is joined to St. Andrews by a sandbar that is exposed only at low tide. Every Sunday, with his wife behind him on a pillion, he crossed the bar on horseback to hold services.

The Presbyterians had no church of their own and Andrews let them use his. Then, at a public dinner, a member of his flock who had imbibed too much Jamaica rum declared that the Presbyterians, being Scottish, were “too mean to build a church of their own.’’ Up sprang a furious Scot, Christopher Scott, from Greenock, sea captain and trader. He announced that the Presbyterians would have a church that would put that of the Anglicans to shame, a church just like that in Greenock—and he would pay for it himself. Greenock Presbyterian Church at St. Andrews, with the green oak of Greenock carved on its white façade, is now as quaint and attractive as any church in Canada.

St. Andrews flourished in the first half of last century. At one stage its population reached six thousand, which made it one of the important centres in British North America. It had sawmills, shipyards and Canada’s first paper mill. Its fine natural harbor was busy with sailing vessels and it exported fish and lumber to the West Indies and Britain. John Wilson, who owned ships and mills, had a manor house surrounded by a deer park, and several other dwellings were almost as impressive.

Like neighboring towns in both Maine and New Brunswick, St. Andrews refused to take part in the War of 1812, but the British constructed a series of wooden blockhouses there. Guns that shot twenty-pound balls were mounted on the walls, but none was ever fired and all the balls, much later, were lugged off as souvenirs by I tourists. The main effect of the war of 1812 on St. Andrew-s was that the community for the next fifty years had a British garrison whose dashing young officers were much admired by the local girls.

Henry Goldsmith, a nephew of poet Oliver, and a poet of sorts himself, drifted into the town in its early days with his wife and six children. He had decided to abandon literature and start a sawmill. He rented ^ shack for his family and went off to raise money for his enterprise. This took so long that Mrs. Goldsmith and the kids had nothing to eat but wild berries and clams they dug on the sand flats. Then Mrs. Mehetible Calef, the doctor’s wife, took them in. She must have been pretty tired of Goldsmiths by the time Henry reappeared. He had been gone six months. Henry never did get his mill going and he finally packed up his brood and sailed for England.

Another oddity, whose real identity is still a mystery w-as Charles Joseph Briscoe. That, at least, was the name he used. He had no visible means of support but was seldom without funds. He rode through the streets of St. Andrews on a white horse, sitting in the saddle with royal dignity, and let it be known that royal blood flowed in his veins. When he died he left instructions that his private papers, which were in sealed envelopes, should be buried with him; then he wanted his grave opened in fifty years and the papers read by officials so that his identity would be revealed. There was great excitement the day the grave was opened, but the papers were so mildewed and faded nobody could decipher them. The only clue was an ivory miniature of King George IV. This prompted the theory that he was a son of George and Mrs. Fitzherbert, who were secretly married.

St. Andrews hoped to be the chief Atlantic port of British North America and by 1835 John Wilson was proposing a railway to Quebec. He even imported laborers from Ireland to build it but his scheme failed. Saint John and Halifax, picked as the eastern terminals of the transcontinental railway lines, became the ports. Although a branch line was later run into St. Andrews, the town by then had begun to wither and its population was declining.

In the lS60s a number of its large houses were for sale for a song. Two were bought by Sir Charles Tupper and Sir Leonard Tilley, both Fathers of Confederation, as summer places. Tupper and Tilley were the forerunners of the summer folks.

In 1888, when the future of St. Andrews looked bleak, Boston promoter named Cram organized the St. Andrews Land Company and a forgotten rhymester wrote:

Capitalists from Boston

Hava said. “We’ll buy the town.”

And millionaires from Calais

Have planked their money down.

The St. Andrews Land Company, backed, as the verse suggests, by investors in Calais, Me., built The Inn, as the Algonquin was originally called. Then in 1890 two extraordinary met visited St. Andrews. One was Willian Cornelius Van Home (later Sir William.), the other Thomas George Shaughnessy (later Lord Shaughnessy) —the second and third presidents of the CPR. They relaxed in the cool salt breezes of St. Andrews, were enchanted by the scenery, and resolved to make the place their personal playground.

Van Home purchased Minister’s Island: Shaughnessy bought Fort Tipperary, the quarters of the British garrison. The CPR purchased The Inn, christened it the Algonquin Hotel and tacked two wings onto the building.

A Moon By Breakfast

On his island Van Home spent a fortune creating the most flamboyant and luxurious seaside haven in Canada. The mansion there is so big-you could easily get lost in it. The Indian mg in the living room is so heavy that eight strong men are needed to lift it. The granite fireplaces in the main rooms are fifteen or twenty feet wide and at either side of these are ornately carved Italian pillars, covered with gold leaf. In the living room there’s a grand piano fitted with a player attachment—Van Home liked to sit and pump the pedals while he gazed through the windows at his gardens.

On all the walls there are huge pictures with gilt frames, at least half of them painted by Van Home, one of the most enthusiastic and prolific amateur artists this country ever had. His studio is still there, just as it was when he was alive, with his paints and brushes in a massive oak chest—an Italian antique which bears the date 1642.

Van Home had boundless energy and seldom slept more than two or three hours. One night when entertaining friends he announced he intended to stay up and paint the moon shining on Passamaquoddy Bay. Next morning when they came down for breakfast the picture, finished and framed, was hanging in the dining room. It’s still there, four feet by five.

Scooped out of solid rock on the island shore below a cliff is a swimming pool. A stone tower with a circular stairway rises to the top of the cliff.

When Van Home died in 1915 his daughter Adeline, a huge jolly woman, summered at St. Andrews until her own death after World War II. Minister’s Island will be inherited by a great granddaughter of Sir William when she comes of age. Meanwhile it is rented each year to Thomas Mathis, a former New Jersey senator, and his brother in-law Maja Berry, a former judge, both of Toms River, N.J. They ban the sight-seers whom Adeline had always welcomed.

The Shaughnessy estate, far more modest than the Van Home, is now the home of the Hon. Marguerite Shaughnessy. Shaughnessy retained part of Fort Tipperary, but tore down the officers’ quarters and barracks and built an impressive residence.

As for the Algonquin, the hotel which was the pride and joy of Van Home and Shaughnessy, it operates only from June to September and has rarely shown a profit. The original structure was burned forty years ago and was replaced by a much more elaborate and fireproof building, to which there have since been additions.

The rates at the Algonquin are steep, up to twenty dollars a day. But, at the height of the season, it has to turn business away and, according to the manager, Pat Fitt, the guests stay longer than at any other hotel in Canada. The regulars who come year after year generally remain for six weeks or two months.

The hotel’s Sunday evening buffet suppers are a St. Andrews institution and draw most of the social set. The wives of the rich appear sparkling with diamonds and decked out in the more expensive creations of Dior, Fath and Schiaparelli.

Algonquin guests swim in Katy’s Cove, an arm of Passamaquoddy locked in by a dam. There, the notoriously cold water of Passamaquoddy is heated by the sun, and a string orchestra serenades the bathers.

Besides the Algonquin and the Commodore, St. Andrews has smaller places like Forest Lodge, a spacious homestead converted into an inn.

The vacation trade is the town’s economic mainstay. The rich employ more than a hundred hedge trimmers, gardener» and handymen, keep the Algonquin humming, and spend so freely that the sales volume of the merchants doubles in July and August. And thousands of tourists who aren’t rich flock to St. Andrew’s to have a look at the celebrities and peep through the cedar hedges at the mansions. Most of the notables discourage them with icy stares and no-trespassing signs, but Senator Cairine Wilson likes to see the visitors have fun. She leaves the gates of Clibrig open. Her estate has two miles of drives which wind through rows of tall trees past gardens, orchards and duck ponds.

The shops of St. Andrews aren’t striking from the outside but, in a way, they are a tourist attraction too. O’Neill’s grocery store, which dates from 1823 and is called the Modem Food Market, is a case in point. It displays delicacies from all parts of the world—Dutch meats, French truffles, j Russian caviar, green turtle soup from the West Indies flavored with Spanish wine, orange-blossom honey from Florida, ravioli from Italy, cheeses from half a dozen countries, and everything imaginable to mix or eat with drinks.

A few doors away at Cockbum’s drugstore there are shelves of costly and exotic perfumes—not the kind usually stocked for a community of fourteen hundred.

Fraser Keay, the mayor of St. Andrews, and Jack Stickney both have china stores with plates priced up to fifty-five dollars apiece and dinner sets priced up to two thousand dollars. Stickney’s shop was started by a relative who wore, on special occasions, a silver suit. For extra-special occasions, he had a gold suit. Among the summer folks of his day was Charles Bonaparte, great-grandnephew of Napoleon, and they vied with each other in sartorial splendor. Charles had a white umbrella.

Another St. Andrews store keeps scores of farm women in funds. It’s the Charlotte County Cottage Craft, an organization run by Kent and Bill Ross. They took it over in 1945 from Miss Grace Helen Mowat, who launched it thirty-five years ago with capital of ten dollars. She revived weaving and other handicrafts among farm wives, supplying them with designs and raw materials and paying them for their finished work. Today it is a thriving enterprise.

Grace Mowat, who has had two books published, is one of St. Andrews’ three authors, the others being David Walker and Guy Murchie. St. Andrews also has more than its share of scientists for it’s the site of the chief fisheries biological station on the Canadian Atlantic coast, with a permanent staff of twenty-five biologists.

Another of the little town’s claims to fame is that it is the biggest lobster shipping centre in North America. Conley’s Lobsters Ltd., founded more than a half a century ago by Edward Conley, who is now in his eighties, buys about six million pounds of live lobsters a year and expresses them as far away as the Pacific coast. Most of the hotels, restaurants and night clubs in Canada and the U.S. serve Conley lobsters.

In the summer in St. Andrews the natives are too busy catering to vacationists to enjoy the weather or the scenery, but in winter, when the Algonquin and all but a handful of the mansions are shuttered and empty, they relax, and groups like the St. Andrews Music, Art and Drama Club come to life. This club won the award for the best costumes in the 1952 National Drama Festival.

The natives prefer the winter. “Summer folks,” one of them explains, “are wonderful people. They’re “u” bread and butter. But the kind we get here can pay for service and want a lot of it —and giving service can tire you out.”

The late Jack Ross, a barber, used to close the season a bit early—unofficially, of course. By mid-August he’d start sitting outside on the steps of his shop, trying to look as though he didn’t know the difference between clippers and a mowing machine. If a stranger asked him when the barber would be in he’d shrug unhappily.

“I couldn’t say.” he’d reply. “That fellow’s so darned unreliable you can’t depend on him at all.” ★